Possible idea

almost 2 years ago

– Tue, Dec 06, 2022 at 03:50:33 PM

This post is for backers only. Please visit Kickstarter.com and log in to read.

The personal side of Dwiggins. Cool stories, published together for the first time. Tons of never-before-seen art, much in color.

This post is for backers only. Please visit Kickstarter.com and log in to read.

Hello Everyone,

Gray had finished the first batch of deluxes! Although it is a nine-hour round trip to drive over there, in keeping with my desire to maintain direct, physical contact with everyone on the team, I'm going over to Gray’s studio in Maine on the 11th to pick them up in person. My partner Sylvia has generously offered to keep me company and share driving.

We’ll read aloud as we often do on long car trips. Our current book is the WAD-designed Knopf edition of Thomas Mann’s The Black Swan but we’re almost finished with that; I have to pick out a couple more titles from the WAD bookshelf for us to take along. Robert Nathan is one of our most favorite WAD/Knopf authors but by now we have gone through all of his books. Plenty more to choose from, though.

When I am back from Gray’s I’ll pack deluxes and posters into the Priority Mail medium boxes and get those out to you. (And in some cases will include standard copies as well.) Given that there are twenty-five of these to do, with my carefully wrapping each book and then packing it with appropriate padding into the box, this is not something I wish to do in a hurry, and therefore I am not likely to pull this off in one day, so they'll be going out in the mail around the 13th or 14th. For US recipients that should mean delivery toward the end of the week, or Saturday. For international, I have no way to predict delivery times . . .

I’ve had very nice feedback from some who have already received their standard copies via media mail, and more books are arriving every day. Your thoughts and comments are always welcome. I hope as you dive into the stories, you will find the same pleasure and positivity in them that I do. And as always, thank you, each one of you, for helping to bring this book into the world. WAD must be very happy about this.

Greetings All,

Sylvia and I drove over to Maine so that we could spend the day yesterday helping to wrap and ship out standard copies of the book to all of you who backed at that level (plus books and posters to backers outside the US). I am very pleased with the appearance of the lithowrap binding and Superior did a great job lining everything up.

Penmor set up an area in the pressroom where we could work comfortably, just as they did in 2018 when I was there for several days to help with packing and shipment of “W. A. Dwiggins: A Life in Design.” I delight in being in that building and feeling around me the quiet, competent energy of this crew that cares so much about doing work carefully, thoughtfully, efficiently. Quality and pride a daily part of life, not just slogans on their promotional materials.

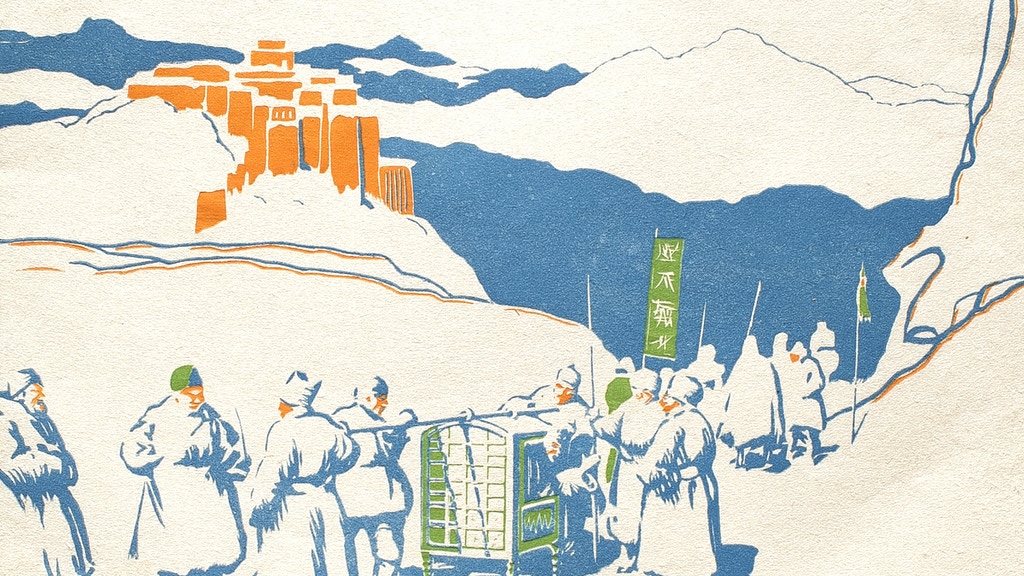

With me in this picture is Jeff Richardson, who is the inside person on every job I do with Penmor. He takes care of the tiniest details of production once a project has entered the system and has a job ticket. I've worked with him for decades and love that he combines an enthusiastic and fun demeanor with an absolute steel-trap mind.

Packages will go out Monday via Media Mail to US addresses. Everything outside the US will go via US post office shipment. I'm grateful to one of the Canadian backers for alerting me to the aggressive fees/charges made by UPS to recipients, for incoming shipments from the US — we were able to change over to USPS so with luck all those packages will get to Canada without any “surprises.” Thanks, Chester!

Gray Parrot is still expecting to have the first batch of deluxes ready in December, so I'll drive over to his place in Warren to fetch them and will mail them out once I am back in Vermont. (It's a 4-hour drive each way to go to Penmor or to Gray, but I really like the personal contact.)

I hope each of you will be pleased when your book arrives. Let me know immediately if you have any issues or disappointments. And thanks again for helping to make this happen!!

Hello Everyone,

I am away until this coming Wednesday but have learned from Penmor that the books have arrived there from the bindery! So the current plan is that I'll go over to Maine on Friday to help with the packing and shipping. Books will leave Lewiston Friday or Monday and will travel via Media Mail to addresses in the US, so will probably take seven to ten days to arrive, depending on how far away you are from Maine. Books to Canada will go via UPS and I have *no* idea how long those will take! Books to the rest of the world will travel via USPS International Priority Mail and again, I cannot tell you when you'll see them. But it'll be soon.

Thanks again to each of you for helping to make this book a physical reality. I know WAD is up there whistling tunelessly, with a grateful twinkle in his eye.